Editor’s note: this is a guest post. The author’s bio can be found at the bottom of the article.

I chose to publish another article about ‘A Death in Malta’ because I find it to be a relevant, refreshingly honest piece. It is also timely that this piece is published on the 76th monthly anniversary since Daphne Caruana Galizia was assassinated.

I’ll be attending tonight’s vigil in her memory, I hope to see a few familiar faces.

***

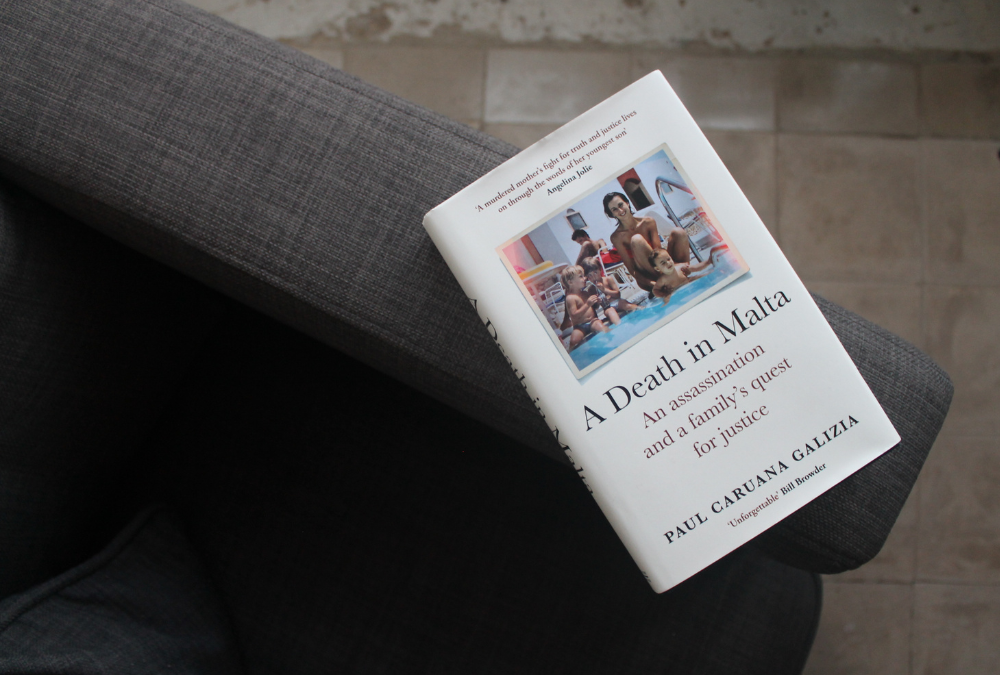

‘A Death in Malta’ is not a page-turner. Its pages make you want to do the exact opposite – you feel afraid of what’s lurking on the next page.

Perhaps, it is because so much of what Paul Caruana Galizia wrote is familiar, or so we all thought. Turning from one chapter to the next is not exciting, it’s stomach wrenching. We are familiar with the filth, the context of corruption and sleaze in which this tragic story transpires, so that might explain it.

It’s a very addictive book, of course. Like eating spicy food – the more it burns, the more you need to stuff your mouth with it. I can’t find a better comparison. That’s how this book reads in my head.

While I now feel slightly ridiculous just thinking about it, I’ll admit that when I reached chapter 12, I had to take a breather. From the very beginning of this chapter, I knew that this was the one that would describe when Daphne was killed with a bomb placed right under the driver’s seat.

I got that indication because Paul divides the chapter into minutes. 2pm, 2:35pm – I knew what was coming. And because I knew what was about to transpire in the words thereafter, I was in pain. Daphne was not my mother, so I cannot begin to imagine what Paul, Andrew and Matthew had to go through, and have to go through now that this cruel bit of their story is immortalized in a gripping book.

I remember as I stood up from my sofa, uneasy. I had to close the book, as if that would somehow shut the words written on it behind its bounds and not let any more of it escape the cover.

I was also a bit disappointed in myself. It was a beautiful Sunday morning, the sun rays violently hitting the tiny reading corner of my flat, my preferred spot to indulge in a good, thick book. I had happened to reach its most violent chapter on my reading morning, and I simply couldn’t go on. I’m sure I wasn’t the only one who experienced this.

I’m familiar with interviews featuring Matthew as he tells the story of how he walked among his mother’s body parts, and of course I knew this piece of the story was going to be included here. Still, the details that emerge here are heavy, despite the fact that Paul writes most of this chapter in a pragmatic, almost clinical manner.

While the horrible details of the assassination forced me to put the book down when I couldn’t handle it, it also revealed pleasant things about Daphne. Now, I can’t listen to Bob Marley without imagining her jiving to the sound of Concrete Jungle. Apparently, she was an avid fan of his greatest hits.

I was aware of her love for the garden. But the constant referencing to the different plants and trees in her garden in Bidnija offers a beautiful sense of relief.

Perhaps Paul does this to remind us of just that – that Daphne was beautiful and full of life.

I couldn’t help but go on the internet and hunt down every piece of video that features Daphne. I wanted to hear her voice and compare it with Paul’s description of her. You know, like when you watch a biopic and go online to look for the real footage.

I also ended up going back to her blog, to the videos of the Labour Party winning the elections, of Joseph Muscat and the lot. I couldn’t look at the online pages that demonized Daphne, nor could I read the barrage of filth that the government spewed out to dehumanise her. In what now feels like my other life as a journalist, it is a part of history I was exposed to and do not want to revisit.

Now I understand, more than ever, how this assassination began. Demonisation. Remove every human element from Daphne, and she’d be ripe for the picking. Because it’s easier to kill a ‘witch from Bidnija’ than a mother, a wife, a daughter.

The book also left me with some guilt. I am one of the many journalists who decided to pull out of the game just before it got to my head too much. So to me personally, this book put me slightly to shame. My only consolation that allows me to sleep at night is that I am still involved in organizing protests here and there, and through my work with JRS Malta, I advocate and campaign for the rights of migrants – another segment of our society that is constantly dehumanised.

It also reminds me of one of Daphne’s earliest posts – she was right about the conditions within the detention centres in Ħal Far and the systemic problems that have plagued our detention regime for more than two decades.

A Death in Malta is a necessary read. The first few chapters alone go through our island’s history in such an open manner, that, although it might look over simplified, it’s the relevant history we need to know before going to vote, or before trying to understand the country’s complex political shitshow, our tribalism, and the views of the migrant other.

Gabriel Schembri is a freelance journalist, book author and communications coordinator for a human rights NGO.