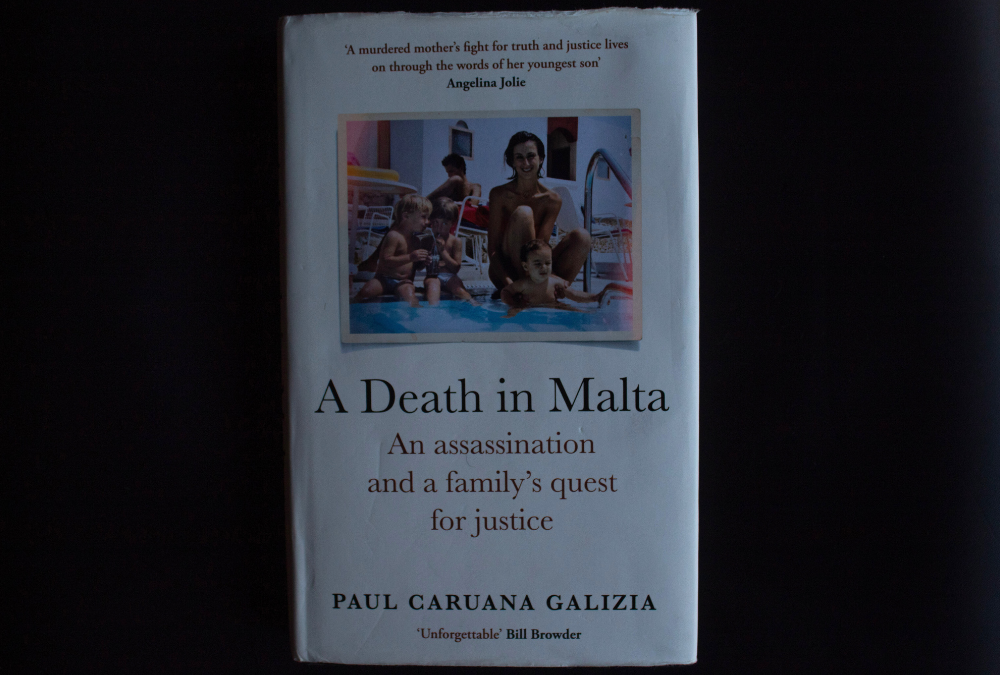

I must apologise to the author of A Death in Malta: an assassination and a family’s quest for justice, Paul Caruana Galizia, for not managing to read his truly unforgettable book sooner. Although reviewers near and far with much greater acumen than myself have already showered the book with much deserved praise, I feel compelled to add my voice to the chorus, and perhaps share some of my own thoughts that popped up as I read through it.

I’ll do my best to avoid spoiling it for you, but if you were considering picking up a copy, I would urge you to do so before reading this column. I can assure you that you will not regret doing so, and would happily forfeit your readership of this specific column if it means you go directly to the book itself.

Paul’s writing is both clinically precise and wonderfully meandering. It is a beautiful example of a happy marriage between loose, anecdotal recollections and a rigorously researched narrative that took the author around four years to pull together. The various threads which, at first, the book seems to pick up haphazardly, come together perfectly by its end, leaving any reader with a pulse and a functional conscience absolutely breathless in the process.

I began my career as a journalist after Daphne’s murder. I admired her journalistic skills, her caustic wit, and her resoluteness before she was murdered, even though I’ll be the first to admit that, as a dumb but very angry teenager, I was not immune to the insane amount of propaganda that was constantly churned out to defang her work and intimidate her into submission.

After she was murdered, a new kind of counter-propaganda emerged: Daphne became a martyr. Her face became a stencil whose outline is so familiar I feel like I could almost trace it blindfolded by now.

Paul’s book reminds us of one particularly important thing which, as he says, even the most avid of her supporters would sometimes forget about – Daphne was a human being who gave up the best parts of three decades of her life in service to a country that never made her feel welcome, a country that largely failed to understand what she stood for and why she wrote the way she did throughout her illustrious career.

‘A Death in Malta’ reminds us that behind the awe-inspiring bravado which adorns her scathing Sunday columns and running commentary, there used to be a woman who was beloved by her family and was treasured by a circle of loved ones that kept getting more and more restricted towards the end of her life. The massive wave of anti-Daphne propaganda that the Labour Party was at the centre of had served its purpose – by 2017, both major political parties were doing their utmost to crucify the one journalist they could not control, coerce, or intimidate, leaving her completely isolated.

In fact, the public inquiry – which Daphne’s family had to relentlessly campaign for before Muscat was left with no option but to set it up – clearly outlined how there was “an orchestrated plan” to neutralise the political impact of her work, a plan “which was successful because it was orchestrated by the Office of the Prime Minister”.

This book sheds much-needed light on the fact that Daphne did not just suffer a brutal demise at the hands of a mafia state. She suffered throughout her entire career, and endured the fear, the anxiety, and the pain it all brought out of a sense of duty towards the same country which effectively exiled her to her own backyard.

Daphne was indeed afraid. And yet, she fought and fought and fought, all the way to the bitter end. Although I’m quite sure she would have hated the fact I’m using this commonly butchered aphorism, I nonetheless think it is appropriate to point out that “courage is not the absence of fear, but rather the judgement that something else is more important than one’s fear”. Daphne made that judgement call, day in, day out, year after year.

Besides wanting to shine a small spotlight on the book itself, I also feel that, given that the main antagonists in the story are yet to be reached by the haplessly short arms of the law in Malta – including the eternally disgraced trio, former prime minister Joseph Muscat, his former chief of staff Keith Schembri, and former energy minister Konrad Mizzi, none of whom have yet been charged with high-level corruption – Paul’s book is more relevant than ever.

While the alleged mastermind behind Daphne Caruana Galizia’s murder, Yorgen Fenech, has been held under arrest since November 2019 after he attempted to escape Malta aboard his yacht and has been ordering his lawyers to do somersaults in court ever since, two of the three hardened criminals who executed the murder, brothers Alfred and George Degiorgio, have spent the past two years making big claims in an attempt to extort personal advantage in exchange for information which they claim will implicate high-profile former government executives.

Meanwhile, the third hired killer – Vincent Muscat – along with Melvin Theuma, who was the middleman between the alleged mastermind and the hired killers, were both awarded a presidential pardon to testify about their involvement in Daphne’s murder. The Degiorgio brothers claim that Muscat and Theuma are singing from a hymn book that was dictated to them by the same former government executives whose beans they want to spill.

In simpler terms, rule of law in Malta has crumbled to the point where two self-declared murderers actually have the audacity to hold justice hostage by deliberately withholding information while claiming that they do not wish to “testify for free“, where a disgraced former prime minister who oversaw the most corrupt administration the country has ever seen got to handpick his successor (who previously served as his consultant and is just as dirty as he is), where the same disgraced former prime minister’s deeply corrupt henchmen are still free to roam the streets as if they never got caught red-handed sitting on a whole offshore network which they built to stash money they should not have.

Now, Joseph Muscat, evidently unable to sit easily with his conscience and the multitude of court fueled nightmares headed his way, is attempting to make his political comeback at the behest of his deeply desperate successor. Every favour he’s ever been owed is being called in and his public relations machine is in full swing with the complicity of the same tired old faces spewing puff pieces on his behalf. Muscat still seems to think that he is too big to go down.

In reality, the Labour Party ran headfirst into a wall and is too blind to notice just how much blood is gushing out of its wide open forehead.

Let’s grace the argument by following the logic that underpins it – let’s say Muscat decides to throw his hat in the ring and manages to be elected by a landslide. Then what? Muscat’s would-be immunity as an MEP would only remain in place until European Parliament decides it won’t. It is a feverish pipe dream that does not in any way, shape, or form protect him from his government’s past and present crimes.

There is no blanket protection that can keep Muscat safe, simply because he was involved in far too many corrupt schemes. Even with the most complacent police force in Europe and an attorney general that is not fit to hold a candle steady – let alone prosecute major criminals – it is statistically unlikely that at least one of those schemes won’t inevitably catch up with him.

The only thing that could keep Muscat safe from prosecution is if the Labour Party manages to keep its stranglehold on the country’s authorities, and it is evident that the party’s grip on those authorities, once vice-like and seemingly everywhere and nowhere at once, is becoming looser with each and every passing day.

The more belligerent and disingenuous prime minister Robert Abela becomes, the more people are reminded that beneath the slick slogans and choreographed videos lies a disturbing horror, the same disturbing horror that enabled Daphne Caruana Galizia’s assassination, the same horror that enabled all the environmental destruction we see around us, the same horror that exposed the country to so much dirty money so quickly that not even the European Union’s key regulatory bodies managed to notice on time.

This disturbing horror rules over us still. But it rules over us only if we throw our hands in the air and say “I give up” without even bothering to determine whether we’ve done enough, whether there are things we should have done better, whether we really just want to accept things as they are while blaming others for failing to see how bad the situation is so we can feel better about our own lack of action.

There is another part of the aphorism I quoted earlier which is just as important as the part which defines courage. I will leave it here below for you to consider.

“…cowardice is a serious vice. Courage is not the absence of fear, but rather the judgement that something else is more important than one’s fear. The timid presume it is lack of fear that allows the brave to act when the timid do not. But to take action when one is not afraid is easy. To refrain when afraid is also easy. To take action regardless of fear is brave.“