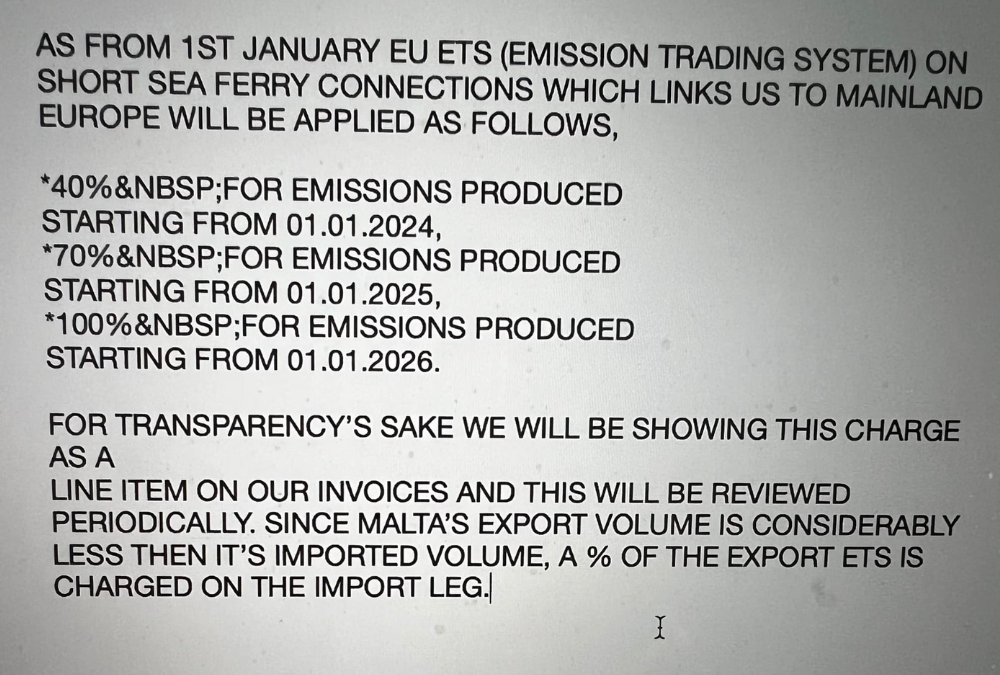

On Thursday, former Nationalist MP and criminal lawyer Jason Azzopardi posted a screenshot on Facebook. The screenshot shows an excerpt of an email that was sent to local businesses from an unnamed Maltese freight company.

“As from 1st January EU ETS (emissions trading system) on short sea ferry connections which links us to mainland Europe will be applied as follows – 40% for emissions produced starting from 01.01.2024, 70% for emissions produced starting from 01.01.2025, 100% for emissions produced starting from 01.01.2026. For transparency’s sake we will be showing this charge as a line item on our invoices and this will be reviewed periodically. Since Malta’s export volume is considerably less than its imported volume, a percentage of the export ETS is charged on the import leg.”

Describing the expected impact of the new carbon tax set to be imposed by the European Union come 2024 as a “bomb that is going to land on all of us”, he also accused the government of failing to negotiate an adequate derogation to cushion the blow as well as failing to provide adequate financial incentives for shipping companies to reduce their carbon footprint, thereby reducing the financial impact on their profitability. Azzopardi’s warning was not the first one to do the rounds.

Throughout the last two months, the General Workers’ Union (GWU) also sounded the alarm. Nationalist Party candidate Peter Agius, along with Nationalist Party MP Ivan Castillo, have also been raising concerns about the carbon tax which is set to be imposed on every ship that enters an EU member state port. The idea behind the tax is to impose a financial obligation on shipping companies given that they are known to be one of the largest sources of greenhouse gas emissions in the world.

Besides current and former representatives of the Nationalist Party and the GWU, similar dire warnings were made by industry leaders quoted by Malta Today. Italian shipping company Grimaldi Euromed has already announced a price hike to offset the tax. Two weeks before Grimaldi Euromed’s announcement, the Malta Freeport’s CEO told Times of Malta that such hikes were to be expected, concerns which were echoed by the Chamber of Commerce and the Malta Employers’ Association.

So, what’s the problem in a nutshell?

The key issue highlighted by the individuals and organisations referred to in this story is that Malta, which is especially vulnerable to the financial implications of the tax due to its dependence on the shipping industry, will be effectively avoided by vessels seeking cheaper, non-EU ports to dock into. The implication, therefore, is that the additional cost imposed by the tax will be passed on to consumers in Malta since both imports and exports will become more expensive.

According to the OECD’s expert on shipping and ports, higher taxes on shipping company profits (which on average, pay just 7% tax on their profits), along with taxing heavy fuel oil that is widely used within the industry, would be the ideal way in which to reduce the industry’s impact on climate change.

Overall, a lot has been said about the carbon tax’s expected impact on commodity prices, a nerve-wracking conversation that is occurring in an already tense context fueled by sky high inflation, an absolutely rattled global economy that is still balking under the combined weight of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Israel’s escalation of the genocide it is committing in Palestine, and the long, dragging aftermath of a pandemic. Social media is littered with posts written by people complaining about unaffordable prices with increasing urgency.

Of course, I cannot help but also mention that Malta’s government has been embroiled in major corruption scandals for the past decade and has demonstrated total disregard for the notion of frugality. Instead, the Labour government preferred to disburse hundreds of millions of euros in direct orders to selected loyalists every year while simultaneously further draining public funds by capturing the institutions which were meant to prevent colossal corrupt fiascos like the hospitals deal.

Less has been said about the way in which commodity prices have morphed on a more long-term basis. I wanted to get a clear sense of which commodities have grown more expensive over time and how Malta compares with other countries in Europe beyond the obvious impact of the pandemic, two major ongoing acts of aggression, and an unstable global economy.

I also wanted to contextualise these commodity prices with other key markers of economic and social stability – the government’s surplus/deficit over the years, labour cost levels, corruption, and press freedom. This day-long endeavour culminated in the key findings you can find listed below. The main source of this data is Eurostat. Corruption data was sourced from Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index. Press freedom data was sourced from Reporters Without Borders’ Press Freedom Index.

Briefly explained, eight out of the twelve categories of commodities – including bare essentials like clothing, education, and food – displayed an upward trend in pricing before the COVID pandemic marked the start of an era of new economic woes. The remaining categories registered either a partial or full downward trend.

The indices that these findings draw data from show the price levels of different countries relative to a chosen country or a country group. There are two data charts per category outlined below: one focused solely on the price level index for Malta and one which compares that same price level index with indices from other European countries.

The point of this exercise is to draw attention towards the undeniable link between declining standards of living and the government’s failure to manage the country’s finances in a reasonable, prudent manner.

While I sincerely hope that I do not need to actually state that I am not attributing global crises like the pandemic or the Russian invasion of Ukraine to the Maltese government, I nonetheless feel compelled to point out that problems stemming from soaring commodity prices and a lack of investment in foundational aspects of our society were always entirely predictable and therefore, problems that could have been mitigated in scale and impact.

Key findings

8/12 categories of commodities on an upward trend:

2/12 categories of commodities on a partial downward trend:

2/12 categories of commodities on a downward trend: